Thomas Peace writes a thoughtful reply (here) to my earlier blog post, ‘Drinking one too many on the historical playground’. The debate is over the kinds of language academics use in talking about early colonial North American history. It’s also, from my perspective, about how the way academics work puts them out of touch with both the rest of the world (sometimes with good effect as Peace suggests, but sometimes not) and with the actual history they study.

Let me say that Peace appears, from all I can see, to be a thoughtful, careful scholar. When he says that the recent trends in aboriginal/colonial history are all grounded in empirical research, he is certainly right. And his own work certainly falls into this category.

It is, though, disingenuous to claim that the debate we’re having is between those with more insight into the realities of the past (the current academics) and those who don’t understand the past (the general public and, I suppose, me).

The reason that the history of colonial British and French North America is presented as it is does not solely come from new empirical research. Academic historians now regularly downplay the importance, and the power, of the European colonial powers. They regularly emphasize the agency, power, cunning and intelligence of aboriginal populations. The impact of colonialism is said now to be much more drawn out, to not have had as immediate of an effect as previously thought.

All of this is partly based on new research – research done by Peace himself but also by many other scholars in the field, including the detailed and important work by John Reid that Peace highlights. But it’s not only the research that leads to this assessment.

There are two other key elements at work: politics and academic trends.

Academics tend to reward originality only when it comes in bunches. For the last few decades, there have been rewards (and general acceptance for) work that has built on the key insight that the power of the European colonial powers was not as significant as previously thought. These kinds of insights have rebalanced the field, and filled in gaps in our knowledge.

They also fit with the kinds of politics that are ongoing in the broader society, and particularly with regard to aboriginal peoples. An emphasis on the capacity of aboriginal peoples, their claims to statehood, as first peoples, as carriers of legitimate and worthy cultural traditions, all played out in a context where the legitimacy of treaty obligations and the legacy of colonial era treaties and documents really matter – all of this adds to the history a political saliency. It matters – it can matter – what is found in this remote history. We just have to turn the situation around to see just how much it matters. A historian who argued that particular aboriginal groups were not as culturally, economically and politically self-sufficient would face significant criticism. Someone who argued that a particular aboriginal group did not have the same characteristics as we might associate with being a ‘nation’ would find that there work became politically sensitive and dangerous. This particular past might be long ago, but it is not remote.

And it strikes me that this is why the academic debates and language are now so far out of whack. We have rebalanced the debate only to see it tip far to the other side. This is what I mean about academics having their heads in the clouds. Because we’re so caught up in our own debates, and because these debates are so caught up in contemporary politics, there is very little incentive (and indeed many dangers) in setting the balance right again.

Fifty years ago the general impression one would have taken from much academic and popular history of early Canada was of daring explorers leading the foray into new lands, creating a new nation out of the wilderness. The academic researchers were more inclined to show the warts of such explorers and settlers, but the emphasis on the Euro-North American past was the same.

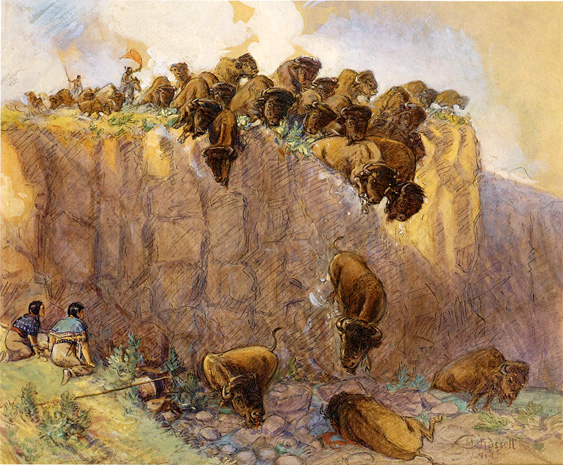

Now, the general impression one draws from reading the history of early Canada is of incompetent, corrupt and weak European settlers and travelers, not making much headway in what was mostly aboriginal space. Gone are the laudatory examinations of the ingenuity of the European adventurers and the cultures they helped to create. In their place, we have laudatory pieces on the amazing technology, local knowledge and capacities of aboriginal peoples.

At the end of his post Peace says that ‘Canada and the United States are legacies from Europe that had to overpower, though not destroy, all other societal alternatives’. But the overall trends in scholarship over the past couple of decades leave one perplexed as to how this could happen. How could such powerless societies, so hampered by limitations on their power ever actually achieve anything? I can’t count the number of times I’ve been in academic audiences when everyone has shared a private joke about the incompetence or naiveté of some colonial official who just ‘didn’t get it.’

Why do historians shy away from talking about the capacity of Europeans to extend power over time and space? Is this only because of new empirical research? Is this about scholarly objectivity? In part, yes. But that's far from the whole story.

My sense is that academics no longer have the confidence or willingness to take the same approach to Euro-North Americans because to do so would make us uncomfortable. If we talked about Euro-North American society in the same way we now talk about aboriginal peoples, we would have to extol the capacities and resilience of those who we now are uncomfortable in claiming as the creators of the nations we inhabit. We are the guilty inheritors of nations whose past we don’t want to own. So instead of owning up to this, academics fret about making sure the language we use is certain to show how limited European power was in the early history and how much more complex the process really was on the ground.

This isn’t empirically wrong. It is even part of a much-need rebalancing. But it is incomplete. The real history is, to use that term all academics love, so much more 'complex.'